How a Welsh Food Protest Echoed into the Age of Rebecca

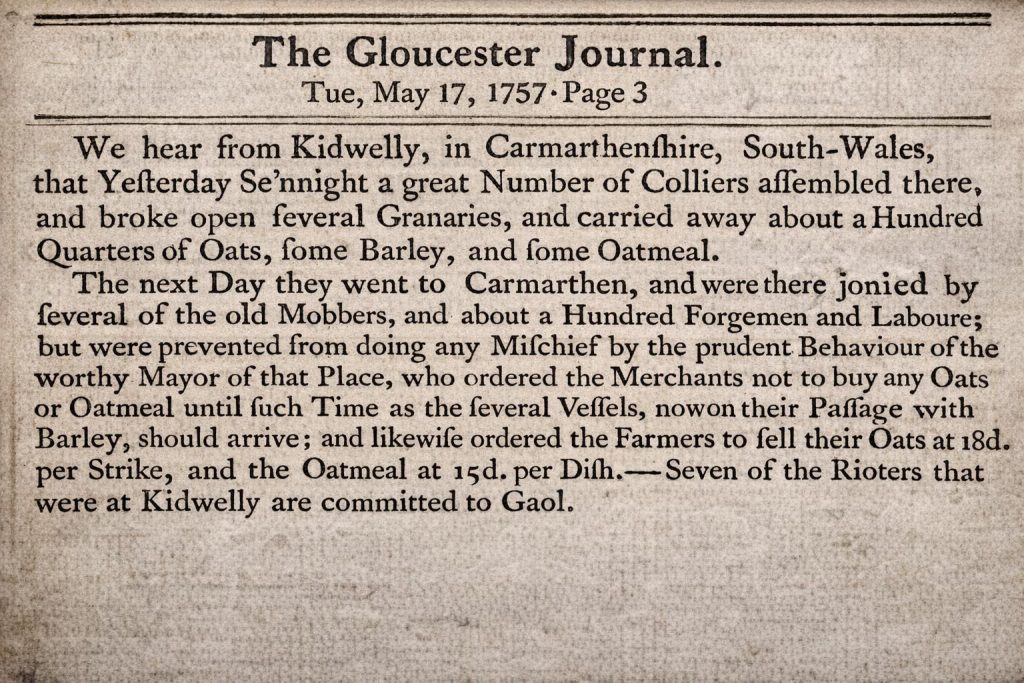

Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire — In the summer of 1757, the quiet market town of Kidwelly became the scene of unrest that revealed deep cracks in Welsh rural society. Sparked by rising food prices and wartime hardship, the Kidwelly riots were more than a moment of disorder; they formed part of a tradition of popular protest that would resurface nearly a century later in the famous Rebecca Riots.

Britain was then in the grip of the Seven Years’ War. The conflict disrupted trade, strained local economies, and drove up the price of basic necessities, particularly grain. In Kidwelly, labourers, small farmers, and townspeople accused merchants and landowners of hoarding corn or selling it outside the district while local families struggled to survive. Crowds gathered to demand that grain be sold at a “just price”, reflecting a widely held belief that the community had a moral right to affordable food.

Unlike modern riots, the events of 1757 were not acts of mindless destruction. Participants targeted specific individuals and practices, enforcing what historians later termed the “moral economy”. Their aim was regulation, not revolution. Magistrates eventually intervened, restoring order while carefully balancing punishment with conciliation, aware that heavy-handed repression could provoke further unrest.

Although the Kidwelly riots faded from immediate memory, the ideas behind them endured. They established a powerful precedent: that ordinary people could collectively challenge economic injustice when authorities failed to act. This tradition of protest remained embedded in Welsh rural culture, passed down through local memory and experience.

When the Rebecca Riots erupted across south-west Wales between 1839 and 1843, many of the same themes reappeared. Once again, communities protested what they saw as unfair economic burdens—this time the tollgates imposed on already impoverished farmers and labourers. Like the Kidwelly rioters, Rebecca’s followers acted collectively, targeted symbols of injustice, and justified their actions through shared moral arguments rather than political ideology.

The methods were also strikingly similar. Just as crowds in 1757 sought to regulate grain prices, the Rebecca rioters sought to regulate tolls, enforcing what they believed to be fairness when official systems failed. Both movements demonstrated a deep-rooted Welsh tradition of popular protest grounded in community rights and economic justice.

Seen in this light, the Kidwelly riots of 1757 were not an isolated disturbance but an early chapter in a longer story of resistance. From food shortages in the 18th century to tollgates in the 19th, the people of rural Wales repeatedly showed that when livelihoods were threatened, collective action became both a weapon and a warning.

Measured Justice After the Kidwelly Riots of 1757

Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire — In the wake of the food riots that shook Kidwelly in 1757, many feared harsh retribution from the authorities. Instead, what followed was a restrained and calculated response that reflected both the realities of the time and a tacit understanding of popular protest.

The disturbances broke out during a period of acute hardship. Britain was at war, food prices were rising sharply, and local people accused merchants and landowners of hoarding grain while ordinary families went hungry. Crowds gathered not to plunder indiscriminately, but to demand that corn be sold locally at what they called a “just price”.

When order was restored, local magistrates moved carefully. The Riot Act was threatened, and in some cases read, but mass arrests did not follow. Only a small number of individuals—those identified as ringleaders—were taken into custody. Even then, punishments were relatively mild, usually involving short spells of imprisonment, fines, or being bound over to keep the peace.

Most of the rioters faced no prosecution at all. Once grain supplies were released and prices eased, many returned quietly to their daily lives. Authorities recognised that the unrest stemmed from genuine economic distress rather than criminal intent, and they were wary of provoking further disorder through heavy-handed punishment.

This restrained approach was typical of food riots in the 18th century. Officials understood the unwritten rules of what later historians would call the “moral economy”: communities believed they had a right to fair access to food, and protest was tolerated so long as it remained focused and limited.

The handling of the Kidwelly riots left a lasting impression. It reinforced the belief that collective action, when directed against unfair practices rather than individuals, could bring results without severe consequences. Decades later, this expectation would resurface during the Rebecca Riots, when Welsh communities again challenged economic injustice with the confidence that authorities might negotiate rather than simply punish.

In 1757, then, the rioters of Kidwelly were not crushed, but contained—an outcome that shaped the traditions of protest in rural Wales for generations to come.

(Article/Image Creation Alfiepics)